Tracking smoke pollution with smart air monitors in the Sutherland Shire

| Dates | June 2023 - ongoing |

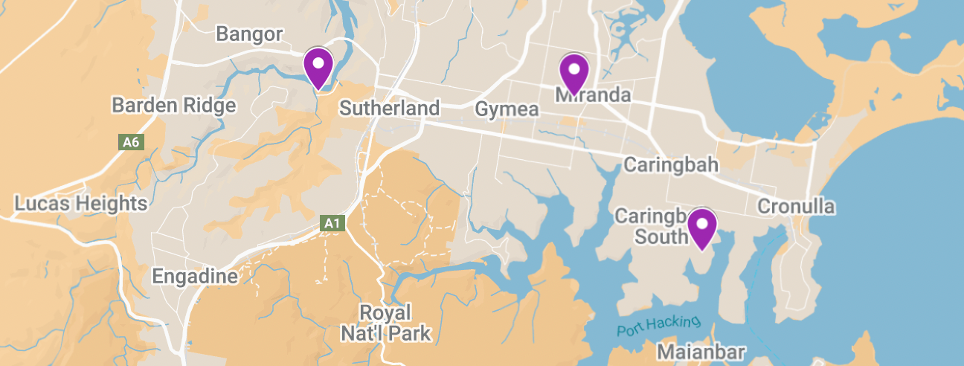

| Locations | Miranda, South Caringbah, Woronora |

| Issue | Smoke from bushfires, hazard reduction burns and wood burning heaters |

| Sensing devices | 3 Clarity Node S air sensors (2 of 3 with meteorology modules) |

| Data measured | Temperature, humidity, wind, particulates (PM2.5, PM10), NO2 |

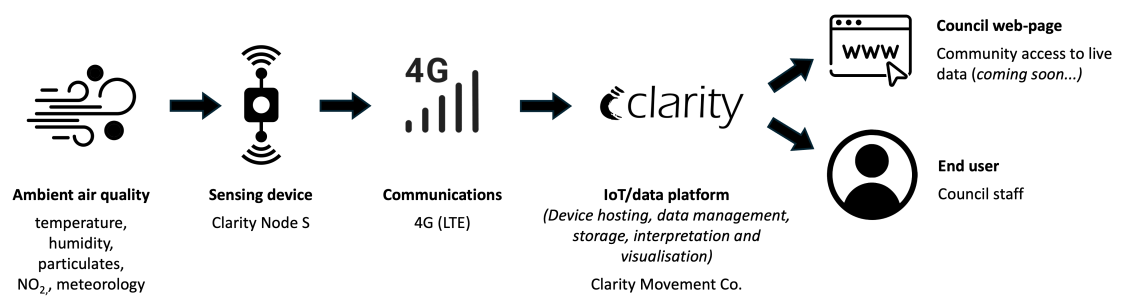

| Communications technology | 4G (LTE) |

“OPENAIR has provided Sutherland Shire Council with a unique opportunity to explore and engage in air monitoring using low-cost smart sensors. Without the funding, and specialist technical expertise and guidance provided throughout the program, it is unlikely that Council’s air monitoring project would have been realised and outcomes so successfully achieved.”

Significant risks to human health and community wellbeing exist from exposure to particulate pollution associated with smoke from bushfires, hazard reduction burns and domestic wood-burning heaters. Through participation in the OPENAIR program, Sutherland Shire Council has installed a network of smart low-cost air quality monitors to measure local air quality at Miranda, South Caringbah and Woronora. The collected data informs and educates the community about air pollution impacts and how to manage and minimise exposure when thresholds are exceeded.

Why did Council focus on this issue?

Growing community concern about air quality, particularly smoke, has been apparent to Sutherland Shire Council since the 2019/2020 Black Summer bushfires. Council’s Community Strategic Plan commits to supporting a beautiful, protected and healthy natural environment. Air quality monitoring is referenced as a critical activity for understanding and responding to air quality issues. More recently, Council has developed a climate change and resilience strategy that provides an additional foundation for the project.

There was also an understanding within Council and from some members of the community that the existing NSW State Government regulatory monitoring network, although high quality, was not providing localised measurements of ambient air quality in Sutherland Shire. This provided an argument for Council investment in low-cost sensing as a way of providing localised data to complement the NSW Govt air quality monitoring network.

Who was involved in the planning and delivery of the pilot?

The project was led by Council’s Senior Environmental Scientist, who is part of the Sustainable Transport and Air Quality team. Administrative support was provided by Council’s Environmental Science unit, technical support came from the Information Management and Technology unit, and practical support for installation of monitoring devices was provided by the Building Operations unit.

The project had direct support from the CEO and Councillors from its inception.

The technology

A priority for Council was that minimal extra work was created for the IT team. They selected Clarity as a ‘plug and play’ sensing option with 4G communications (which works without needing a private network) and solar power (which avoids expensive and complex electrical installation), noting that the devices were robust, weatherproof and had reliable performance.

The Clarity Node S is a mid-performance multi-parameter compact air quality monitoring device that provides near-real-time data at 15-minute intervals, using 4G communications. Its optical particulate sensor, which is critical for measuring smoke concentrations, has a range of 0-1000mgm3 and a 1mgm3 resolution.

All devices were co-located with NSW regulatory monitoring stations for three months prior to deployment and were calibrated to local conditions to ensure data quality. Clarity provided strong active support throughout this process, helping to ensure that Council was confident in the validity of the data that they collected. Devices were connected to the Clarity IoT/Data platform, which provides a range of user-friendly real-time data access, management, interpretation and visualisation capabilities to Council staff. Data is owned by Council and is downloadable from the Clarity platform at any time. Council staff have reported strong satisfaction with the technology, its usability, and the technical support received from Clarity.

Sensing device deployment

Council began with two hypotheses: that bushfire smoke is evenly distributed across the Shire; and that smoke from domestic wood heaters gathers in river valleys due to temperature inversion layers during winter. To test these, two devices were deployed in river valleys at Port Hacking and Woronora Valley, and a third on the ridge at Miranda for comparison.

Challenges and lessons learned

Deployment challenges

Finding appropriate mounting solutions in each location proved to be a key constraint on deployments and took longer than anticipated. Council needed to find Council-owned assets for mounting devices on: with good solar exposure; a minimum distance from roads (avoiding traffic pollution interference); a minimum distance from buildings (avoiding localised thermal interference); and with good passive surveillance (mitigating vandalism). For one location, in the absence of an existing appropriate option, Council’s Building Operations team designed, fabricated and installed a custom pole that met all of these criteria.

“OPENAIR was awesome – it was really critical. It made us more confident about the sensors we were choosing, how we would deploy them, and how to get the best out of them. If you haven't got that input the technical aspects can be quite daunting, and a bit of a deterrent, because you just don't know whether you're doing the right thing.”

– Senior Environmental Scientist

Data and insights

About the data

Council reports that data quality from the three devices met expectations – they trust what they are seeing and are confident about using it to understand air quality in the region. Data consistency has also been high, with negligible gaps in data sets. Council has emphasised the real-time utility of sensor data and the ability to quickly infer highly localised and time-specific air quality phenomena from direct observation. Examples include the behaviour of residents using wood heaters, and marked visual differences in particulate data profiles that enable a distinction to be made between hazard reduction burns and uncontrolled bushfires. The Senior Environmental Scientist also reported an active relationship with colleagues that manage hazard reduction burns and bushfires, allowing correlation of air quality and wind data with records about when and where fires occur.

“When people are putting logs on their fire… at 4 or 5pm, smoke particulate levels go up with a little spike on the graph… then it sort of peters out around 10 or 11pm, and then, boom! You get a second spike, and that's when people chuck their logs on for overnight… you can pick up little tiny nuances like that, which is absolutely brilliant.”

– Senior Environmental Scientist

Key findings

A key finding was that pollution from wood heaters was much lower than expected in both river valleys. Council has inferred a shift away from wood heating due to the price of wood and a widespread uptake of solar and battery technology, which is driving a shift towards electric heat pumps for domestic heating.

A critical element of data analysis involved the use of wind speed and direction data for interpretation of air movements and particulate data. This led to an important insight that ran counter to Council’s original hypothesis. They had expected narrower river valleys to have less air flow and poorer air quality, with smoke collecting and lingering for longer. However, wind data showed that the narrower Woronora Valley had much greater air flow than the much wider Port Hacking Valley. Particulate data showed that smoke from heaters, bushfires and hazard reduction burning collected and lingered for longer in Port Hacking than in Woronora Valley. This insight may change how Council targets communities with air quality education campaigns in the future.

Data sharing

Sutherland Shire Council lacks a discreet data policy that might inform a position on sharing of project data. Decisions about sharing project data were led by Council’s Communications team, via a process of discussion with staff from the IT unit, the Environmental Science unit, and teams that deal with community consultation.

A decision was made to share real-time data with the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water (DCCEEW) via the OPENAIR Pilot Data Platform, which ingests and harmonises data from multiple different air quality monitoring systems. Council is keen to develop an active reciprocal relationship with DCCEEW to extract the most possible value out of the data they collect, benefitting both organisations and the Sutherland Shire community.

With regard to public data sharing, Council chose to develop a live data connection to their website, where current air quality readings for the three sensing locations will be displayed. It was decided that a full public dashboard would likely confuse most people. The aim of the webpage connection is to answer a basic question that people are expected to ask: “is it healthy for me to go outside at the moment?”.

Creating impact

The OPENAIR pilot project has resulted in the following positive impacts:

Heightened awareness, engagement and upskilling of Council staff

The project was internally promoted via the Council Bulletin, and featured prominently in a presentation on air quality delivered to 200 staff in Council’s Planning Division. A more in-depth workshop on the project and data insights was run with 30 staff from the Environmental Science Unit and Health and Building Teams. From informal discussions with staff from different divisions, the project has supported increased awareness of air quality as an issue across the organisation.

Very few people were aware of the health implications of airborne particulate pollution. “For a lot of staff, it was really an awakening about air quality” says the Senior Environmental Scientist. Notably, this awareness within the Planning team is now anticipated to effect land use planning, as planners are now more aware of the impacts of air quality as part of the planning process.

Internal funding secured for ongoing operation of the network

Council’s Senior Environmental Scientist emphasised the positive impact within Council of the OPENAIR Documentary, and the 2024 Banksia Foundation Award for ‘Healthy Planet, Healthy People’. These achievements are cited as adding significant weight to the internal profile of the project as innovative and valuable. This has been linked to securing ongoing operational funding for the sensing network via an increase to the annual budget allocation for the Environmental Science unit.

External engagement

A report on the project and its findings was prepared and made public, with an estimated reach of around 200 people. The project was also showcased to a delegation of around 40 Councillors from Japan, who were interested in air quality.

Looking ahead

Council is finalising the technical integration of live data with their website, which will provide the public with information about current air quality – estimated to be operational by mid 2025. It is hoped that this will support community members to make informed personal decisions about day-to-day activities.

Council aims to maintain the current Clarity network and expand it with the addition of another four sensing devices. This expansion would include deployments next to major roads, enabling exploration of localised air quality associated with road traffic pollution. It is hoped that one of the new devices might be established as a mobile unit for short term ‘pop-up’ deployments, enabling Council to respond to specific localised air quality concerns as they arise.

Council’s Senior Environmental Scientist notes that there is no direct tangible benefit from a monitoring program until a significant air quality event occurs (akin to the black summer fires). In this respect, Council is being proactive by investing in the network. However, ongoing operation and expansion of sensing activities costs money, and building a robust business case for the future remains a challenge. This is exacerbated by the often-complex political dimensions of air quality, from interventions that impact private car use, to the location of schools and community facilities alongside pollution hotspots.

The best recourse, says the project lead, may be the understanding that if you don’t know what’s going then you can’t manage it. Better planning for resilient and healthy communities must be grounded in hard evidence; and data from smart low-cost sensing has the potential to provide that.